Daughter of the Depression

by Judy Haught

Born October 20, 1929, just days before the infamous stock market crash that ushered in the Great Depression, Barbara Blake grew up in one of the most economically and culturally challenging times in U. S. history. Joe and Mayme Patterson Thompson gave birth to their oldest child at home on a farm in the White Flat community near Mangum, Oklahoma. On the edge of the Dustbowl, times were hard and became increasingly more difficult as drought persisted. As dust storms devastated farms and unemployment gripped the rest of the country, Barbara recalls a happy childhood with strong community ties and a close-knit family.

Barbara attended the small country school of White Flat from first through eighth grade. Barbara described it as a beautiful red-brick building. Elementary teachers taught two grades each with first and second grades together in one room, third and fourth grades combined in another room, and fifth and sixth grades in still another room. The school did not provide hot lunches, and Barbara recalls carrying her lunch to school.

From first grade on, Barbara was a curious, scholarly child. She particularly loved her first-grade teacher, Doris Burcham. Miss Burcham had been to Yellowstone National Park and shared her experiences with her students. Barbara yearned to see Yellowstone; it was a big dream for a small child in Greer County, Oklahoma, in the midst of the Depression. However, that dream did come true; when her own children were in junior-high school, she took them to Yellowstone National Park. That trip was just one of the ways that White Flat School left an indelible mark on Barbara.

Barbara’s parents were quite progressive in their approach to their children’s education. As young as five, Barbara began taking expression lessons from a teacher by the name of Mrs. Crittendon. Her mother paid for the lessons by selling cream and butter. With a plethora of schools in Greer County during those years, they hosted academic meets on Saturdays. At just five years old, Barbara entered her first competition with a “reading.” Over the years, she won both gold and silver medals for her efforts.

Another example of her parents’ dedication to providing her with the best educational opportunities came when Barbara entered high school. She had graduated from eighth grade at White Flat School, but the school no longer had a high school. Most of her classmates went to nearby Reed High School. In fact, a school bus transported them to and from school. However, Barbara’s dad felt that Reed focused too much on basketball and not enough on academics, so he insisted that she enroll at Mangum High School. Attending school in Mangum was quite a sacrifice for Barbara’s parents because they had to drive her seven miles to and from school each day.

The first few years of Barbara’s childhood were spent in a home without electricity. She remembers first acquiring electricity when she was ten or twelve years old. At that time, most of rural Oklahoma was without electricity. It was only when President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Rural Electrification Act in May 1936 that rural electric cooperatives began forming to bring electricity to the many farm homes in Oklahoma. By the onset of World War II, the Oklahoma Association of Rural Cooperatives organized to implement the electrification of Oklahoma’s country dwellings. One of the results of the advent of electricity in Barbara’s home was the purchase of a Philco radio, bringing the outside world to White Flat. Barbara’s family listened to news commentator Walter Winchell and the nightly news.

Much of what Barbara remembers about the Depression was weather related. Drought was a menacing reality for farmers. In Barbara’s words, “It was dry, dry, dry.” The dust storms rolled in often, and Russian thistles or what we call tumble weeds covered the fence rows. Anxiety had to have dogged Barbara’s dad as families suffered from ruined and nonexistent crops. She related an incident in the late 1930s when her dad managed to get a wheat crop up and growing. The wheat looked promising and the future bright; then a hail storm dashed his hopes. Hail completely destroyed the crop. Barbara said it was the only time she saw her daddy cry.

April 7, 1936 brought another weather catastrophe. A freak blizzard blanketed the country piling snow as high as Barbara’s house. The snowstorm raged for three days stranding a milk tester from Stillwater at the Thompson farm. Barbara’s dad raised dairy cattle, and a milk tester came monthly for three milkings to test the milk for fat content. While stranded in the storm, he helped Barbara’s dad haul water for the family and livestock. They waded through the storm and carried water for the livestock and family from a well a quarter of a mile away.

The Thompson family added two more children during the Depression, a girl in 1936 and a boy in 1941. Barbara’s little sister became an early beauty pageant winner by garnering the title “Most Beautiful Baby.” As a prize, the family received tickets to a movie in Mangum. They watched Shirley Temple at the Greer Temple Theater. It was Barbara’s first experience of going to the movies.

A lot of Barbara’s memories of the Depression revolve around making do with what was available. Her mother made their clothes from flour sacks. They would trade wheat for flour and pick out the sacks, knowing they would be turned into clothing. Although a doctor was available in Mangum, Barbara’s parents treated minor illnesses at home with such remedies as Vicks Salve and calamine lotion.

This make-do attitude carried over into the community’s sense of humor. Hard times were just a fact of life, so most people tried to make light of the situation with jokes and funny stories. One story that Barbara recalls involves a phantom bit of salt pork. Supposedly people passed that salt pork from house to house to cook beans until one day someone tried to eat the pork only to discover someone else had beat him to it. The storyteller would insert a real person’s name as the culprit.

Another means of coping with the Depression was the Works Progress Administration or WPA. Lots of self-sufficient farmers took temporary government jobs to make ends meet. Barbara’s dad was among them. For a time he worked on a road crew, but Barbara remarked that many landmarks in Mangum were built by other WPA crews including the armory, the library, and the fountains at the courthouse.

As the Depression wore on, World War II loomed on the horizon. December 7, 1941, was a beautiful day in Greer County. The Thompson family gathered around the Philco radio and heard the unimaginable: Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. As a carefree twelve-year-old, Barbara did not really understand what she had heard, and her parents did not explain. They remained quiet on the subject, perhaps because they like many Americans did not fully comprehend the gravity of attack. Barbara knew something was terribly wrong, but it was not until she went to school the next day that she heard more about the attack. All the other students were buzzing with the news.

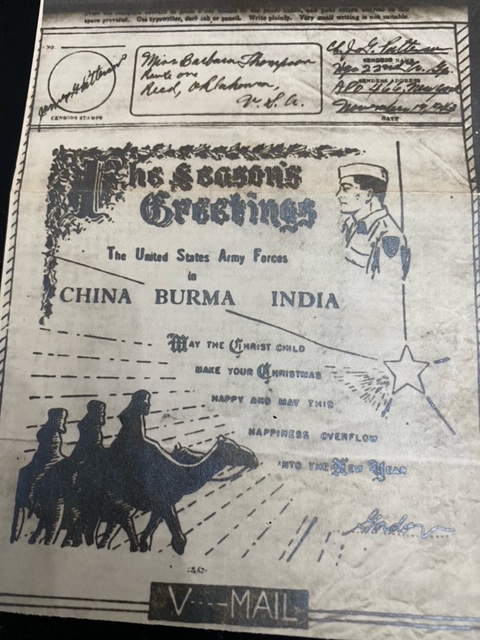

World War II ushered in changes in the Thompson family. Barbara’s mother had four brothers who left to serve in the military. Two served as chaplains, and two fought in Italy. One of the brothers fought with the 45th Infantry Division, was wounded, and was sent to a military hospital in San Antonio. Many neighbors and friends had family serving in the war; in fact, the city of Mangum erected sign on the northwest corner of the courthouse square listing all the men and women serving in the armed forces. Barbara’s church also had a sign listing all who were serving. Barbara described those years as “pretty awful.”

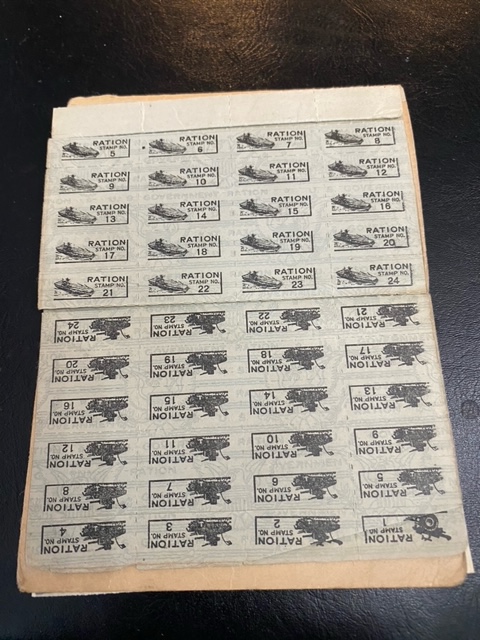

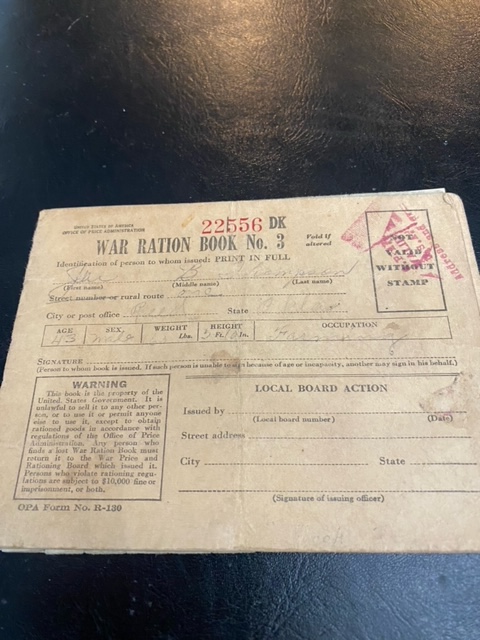

The war also stirred up patriotism among the citizens. They bought saving stamps and war bonds and collected such things as grease, aluminum, and toothpaste tubes. Students took the war effort seriously and did what they could to help or as Barbara said, “anything that FDR asked us to do.” Frugality was the theme, and the government issued ration coupon books for gasoline, tires, sugar, meat, and shoes. People used the coupon books like money, and the need for coupons was a constant worry.

It was during this time that Barbara became aware of the USO and the Bob Hope shows that entertained the troops. News reels at the movies kept people informed about the war and USO efforts. They especially enjoyed seeing Bob Hope’s overseas Christmas shows.

The war ended a couple of years before Barbara graduated from Mangum High School in 1947. She had been dating WWII veteran Lester Blake and wasted no time becoming his wife. Wedding bells rang for her and Lester on June 22, 1947. They raised two children while he worked for the Post Office, but when the children grew up, Lester convinced Barbara that she should attend college. Always a good math student, she decided to become a math teacher. She graduated from Southwestern Oklahoma State University in 1970 and went on to a stellar career in math education in Moore, Oklahoma.

As a child of the Depression and World War II, Barbara Blake grew up during two of America’s most trying eras, but the lessons she learned in rural Greer County prepared her for life’s challenges. Wise, loving parents and a close, civic-minded community created a resilience in Barbara that led to a successful life.