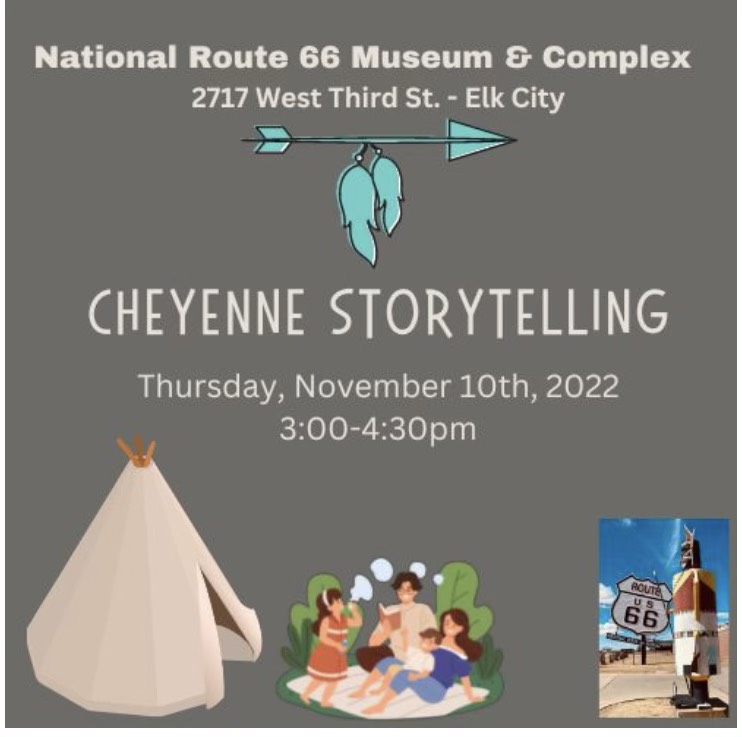

Cheyenne Storytelling Coming to Museum Complex

by Charles Wren

On Thursday, November 10, the Elk City Museum Complex is providing a rare opportunity for visitors interested in learning more about the history of Western Oklahoma’s American Indians. From 3:00-4:30 pm, Chief Wilbur Bullcoming and other members of the Cheyenne Tribe will be present at the tepee, located east of the Farm and Ranch Museum, to teach visitors about Cheyenne history, belief systems, and way of life through traditional storytelling.

Little is written about the Cheyenne. Known in their Algonquian language as Tsistsistas, meaning “The People,” the Cheyenne have a history divided into four periods, the last three of which are named for the animals that altered the Cheyenne way of life as they migrated over the centuries from present-day Ontario, Canada to the Great Plains of the United States.

The first period is known as the Ancient Time. Although its years remain unclear to this writer, in this early age the Cheyenne were an agrarian society living in villages in Ontario and growing corn, squash and beans.[1] As historian Henrietta Mann has written, at some point during the same period the Cheyenne also “had a hunting economy and subsisted on wild game.”[2] This early time reached its end point when a disease epidemic forced the tribe to abandon their settlement in search of a new homeland.

In the second period, known as the Time of the Dogs, the Cheyenne settled in present-day Minnesota, living again as agriculturalists near the Yellow Medicine River in the southwestern part of the state. It was during this period – named after the wolf dogs that followed the Cheyenne as they migrated south – that the tribe first came into contact with Europeans. About five years later, Cheyennes and Europeans held a historic meeting at Fort Crévecoeur in present-day Peoria, Illinois on February 24, 1680.[3]

By the early eighteenth century the third period, the Time of the Buffalo, had begun. This time many Cheyennes were living along the Sheyenne River in present-day North Dakota. Although most continued to farm, others began to hunt bison for the first time, using European steel knives to cut the hides.

Around the middle of the century, the Cheyennes were being pushed out of their region by the Chippewas and began moving south to a region east of the Black Hills in what is today, South Dakota. On the way they were introduced to the horse, thereby entering their fourth and most recent period, the Time of the Horse. The horse brought significant changes to the Cheyenne way of life. By the last quarter of the eighteenth century, most Cheyennes were hunting buffalo on horseback.[4]

It was when Cheyennes were roaming the region east of the Black Hills that the great prophet, Sweet Medicine, entered a cave in present-day Bear Butte mountain, where he received the four sacred arrows from the holy Creator known as The Great One.[5] Sweet Medicine promised the Cheyennes that as long as all four arrows remained in their possession, their tribe would be protected from famine and annihilation. That protection was later be lost when the Pawnee Tribe attacked the Cheyenne in the early 1830s and stole the arrows. Since then, the Cheyenne Tribe has managed to recover only two of the original arrows.

Not long after they had moved into South Dakota, the Cheyenne met the Arapaho Tribe, who had settled in the region much earlier. Instead of fighting over the land, the two tribes joined hands, forming a confederation against other much larger tribes like the Shoshone, who posed a considerable threat from the west. Today both tribes are recognized as one nation, though each one maintains its own ceremonies, traditions, dances, language, customs, and culture.[6]

By the early nineteenth century, the Cheyenne had become notable traders in the Great Plains region. By this time the tribe had also split up into smaller bands, gathering as a whole only during annual ceremonies or other special occasions. In the 1830s some Cheyennes were living between the North and South Platte Rivers of present-day Colorado and Wyoming, mostly hunting buffalo. Other Cheyennes had taken up trapping in addition to buffalo hunting, trading tanned hides to American, European and other white traders for tobacco, guns, and other goods along the Arkansas River in southeastern Colorado.[7]

As Henrietta Mann has shown in her history of The People, “the ensuing years were exceptionally harsh … but particularly to the Cheyennes.”[8] The tribe’s loss of the sacred arrows and the protection those arrows ensured them came only about fifteen years before the rise of the American doctrine of Manifest Destiny and westward expansion. Anyone wishing to get a head start on the history of the Cheyenne Tribe prior to the storytelling event would be interested to read Mann’s book, Cheyenne-Arapaho Education: 1871-1982. A brief history of both the Cheyenne and Arapaho can also be found on the tribes’ government website, cheyenneandarapaho-nsn.gov.

[1] https://cheyenneandarapaho-nsn.gov/project/language-culture/

[2] Henrietta Mann, Cheyenne-Arapaho Education: 1871-1982 (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 1997), p. 3.

[3] Mann, Cheyenne-Arapaho Education, p. 4.

[4] Mann, Cheyenne-Arapaho Education, p. 5.

[5] John H. Moore, “Cheyenne, Southern,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=CH030.

[6] https://cheyenneandarapaho-nsn.gov/project/language-culture/

[7] https://cheyenneandarapaho-nsn.gov/project/language-culture/

[8] Mann, Cheyenne-Arapaho Education, p. 7.