by Judy Haught and Stan Heckrodt

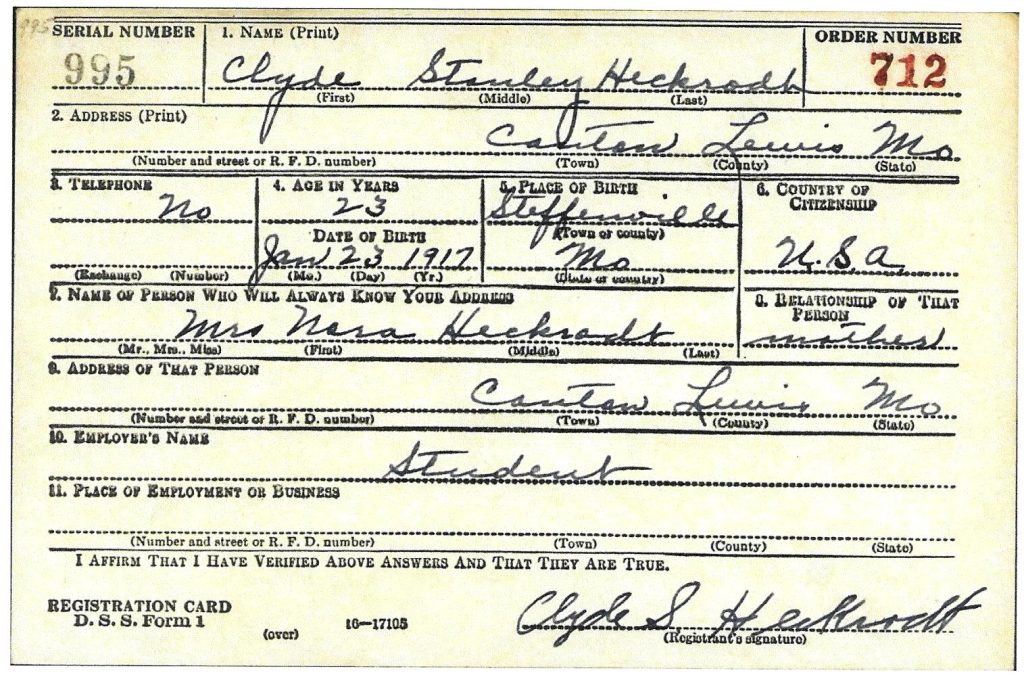

The Great Depression and World War II forged a generation of men seasoned by hardship and steeped in patriotism. Clyde Stanley Heckrodt was such a man. Born January 23, 1917 in Steffenville, Missouri, Clyde Heckrodt came of age in the midst of the worst economic disaster in the history of the United States. On his own from the age of sixteen, Clyde first sustained himself by driving a horse and buggy for a country doctor as he made house calls. Determined to better himself, Clyde continued high school studying at night by the light of a kerosene lamp and sleeping in the doctor’s buggy.

After graduating from high school, Clyde joined the Civilian Conservation Corp or CCC. The CCC was part of Roosevelt’s New Deal that was aimed at pulling the country out of the Depression by granting employment to the millions of unemployed. That particular program employed single men eighteen to twenty-five years old to improve public lands. According to the National Park Service, the men received meals and lodging and earned $30 per month with $25 going home to their families. Most of the men committed for six months of service.

When Clyde Heckrodt completed his commitment to the CCC, he set out to get a regular job, but for every available job, hundreds of men applied. At one job opening, the employer came into a roomful of prospective workers, asked who had a college degree, and sent everyone else home without so much as an interview. Convinced that a college education would be necessary for gainful employment and a better life, he enrolled at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. After completing two years of college work, Clyde’s college career was interrupted. The Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, pulling the United States into World War II. Like thousands of his contemporaries, Clyde felt the patriotic call. He enlisted in the U. S. Navy and because of his two years of college, he was eligible for Officer Candidate School, then flight training. He earned his wings at Naval Air Station, Pensacola, Florida.

The Navy assigned Clyde to a top-secret program that involved what became the forerunner to the modern-day drone. The Navy was flying remote-control aircraft using cutting-edge technology. Because of his work and his security clearance, Clyde was not allowed to leave the continental United States. The secrecy of the operation necessitated frequent moves around the country at a moment’s notice. The Navy could not risk having citizens who could possibly be spies see airplanes flying without pilots. For security reasons, most of the bases to which Clyde was assigned were located in remote, rural areas.

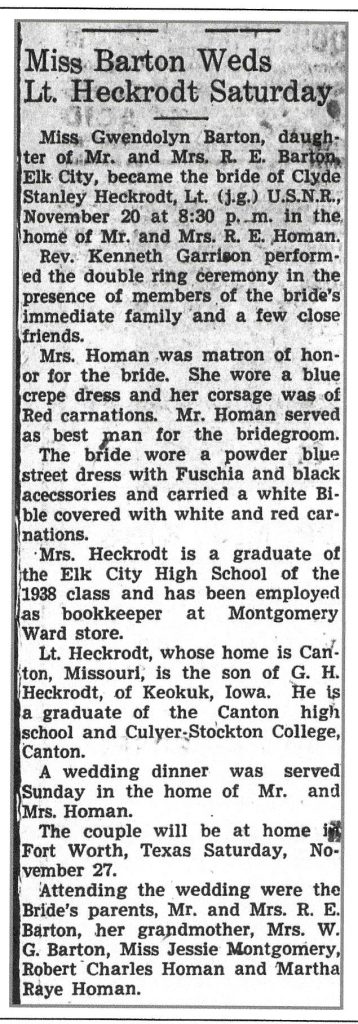

Fortuitously, one of those remote bases was Burns Flat Naval Air Station near Elk City, Oklahoma. During the war, it was common for parties and socials to be held that brought Naval personnel together with single young women from the surrounding area. The local newspapers reported on several such occasions. The mayor of Elk City held a mixer in his home for Navy pilots and invited young women from Elk City. Gwendolyn Barten, a young Montgomery Ward bookkeeper, attended the event. While there, she spied a tall, handsome naval aviator standing across the room wearing his dress white uniform. Knowing she had to meet this man, she crossed the room and started a conversation with none other than Clyde Heckrodt. Gwen went home that night and told her mother she had met the man she was going to marry. Four months later on November 20, 1943, Clyde and Gwen were married at the home of her matron of honor, Mrs. R. E. Homan in Elk City.

As the newlyweds drove away from their wedding, Gwen’s grandmother who had been hiding in the backseat of their car popped up and asked them where they were going. They spent their first night together in a house next door to the home of Gwen’s grandfather where the family proceeded to throw them a shivaree. After the newlyweds had gone to bed, multiple family members showed up in their bedroom with a card table and sat around the bed the rest of the night playing cards.

Gwen moved around the country with Clyde, but sometimes she could not accompany him. During those times, she stayed in Elk City with her parents. When he could get a pass, Clyde would “borrow” a Navy plane and fly to Elk City to spend time with his new wife. There was no airport at Elk City at that time, and because the plane was “borrowed,” he could not land at Burns Flat Naval Air Station, so he landed the plane on old Route 66. Luckily there was very little traffic due to wartime rationing.

When the war ended, Clyde stayed in the Naval Reserve, serving as the unit’s commanding officer until the unit was disbanded in the early 1960s. He had twenty-two years of service and retired as a Lieutenant Commander.

When Clyde and Gwen were first married, he asked her where she wanted to live. Her reply was anywhere but Elk City, but after traveling around the country as a military wife, Gwen changed her mind about Elk City. At the end of the war, Clyde asked her again where she wanted to live, and she chose Elk City. They moved back to Elk City and lived there for most of the rest of their lives.

Clyde and Gwen’s lives encompassed a range of experiences, from the fulfilling happiness of giving birth to two sons, Stan in 1948 and Greg in 1950, to the sorrow of losing premature twins in 1946. As a businessman, Clyde operated various businesses, some successful and others less so. Overall, he had a knack for choosing viable businesses. His first business was the 999 Cleaners. It was family affair with Gwen as bookkeeper, his mother-in-law as seamstress, and his father-in-law as delivery man and general all-around helper. When their children were young, Clyde and Gwen moved to Amarillo, Texas, and operated a Pepsi Cola franchise. Despite their working twelve to sixteen-hour days six to seven days a week, the business was never financially viable. They sold the business and moved back to Elk City and continued operating the 999 Cleaners.

In the late 1950s, Clyde went to work for a construction company that built missile silos for the Atlas Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles during the Cold War. He rose to the position of superintendent, functioning as trouble shooter for the company, making sure that projects that were falling behind or in trouble were straightened out and finished on time. The job involved moving around, a fact that dismayed Gwen. She yearned for a steady home life and a stable environment for her sons, so Clyde left the company and moved his family back to Elk City forever.

Clyde and his next-door neighbor Elvyn Haggard formed a business partnership and opened the H & H Goodyear Store. After a few years, they sold the business and bought Ryan-Elliott Men’s Clothing Store, considered to be the premier men’s clothing store in the area. Clyde continued in that line of business until his retirement in 1986.

Over the years, Clyde was active in local organizations, but his favorite organization was the Masonic Lodge. He became the Oklahoma Grand Commander and was awarded the 33rd Degree Mason Honorific, the highest honorific in Masonry. He also was on the local Masonic drill team, which won the state competition multiple times and was always in the running for the title.

Being adept with carpentry and tools, Clyde bought two older homes and stripped them of useable parts in the late 1950s. He then built Gwen her own home doing most of the work himself. She loved her home and even wanted to return to the house her husband built for her when she was living in an assisted living facility.

Clyde had many pastimes, one of which was working with wood. To that end he bought a bankrupt water ski company and a defunct furniture manufacturer. His sons loved modifying the water skis to their own desires and taking them to the lake every weekend in the summer. The furniture factory provided a way for Clyde to make custom furniture for his family, some of which they still possess.

Clyde’s sons remember camping, hunting, and fishing trips and their yearly summer family vacations where they camped all over the western United States. Stan recounts a story of a time when his father along with his hunting party rescued a group of miners whose cabin had burned down. The miners were stranded in the snow-covered high country in sub-freezing temperatures. Being a modest man, Clyde never spoke of the incident. Stan learned about the rescue from others. Clyde also never discussed the war or anything that would make him appear self-important. Greg recalls an incident that required Clyde to bail out of a burning plane. Again, Clyde was reticent about the seriousness of the event.

While proud of their father for many things, one trait stands out to Stan and Greg. After the war, he went back to college at Southwestern State College in Weatherford, Oklahoma, working days and attending night classes until he completed his Bachelor of Science degree. Stan said, “He never gave my brother or myself any reason to even think that we were not going to college. Education was very important to him. He was my hero growing up, and I can only hope my brother and I have lived up to his standards.”

After his retirement, Clyde and Gwen traveled all over the United States and Mexico in an RV. They also hopped on military transports and flew international until Clyde contracted lung cancer in 1986. After living a full and satisfying life, Clyde died in 1988 at the age of 71.

Clyde Heckrodt was an American hero and part of what has come to be known as the Greatest Generation. More can be learned of his life from the memorabilia left with Gwen and passed on to the Western Oklahoma Historical Society. Digital copies of letters and other items can be seen at https://westernoklahomahistoricalsociety.org/document-category/heckrodt-wwII-collection/.