by Judy Haught

In early 1942, the world was at war. While the United States had declared war after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Lee Clem had other pressing matters on his mind. As a Leedey farmer with aging parents, he felt his place was at home. Nevertheless, the U. S. Army had other plans for Lee, and in March 1942, he received his draft notice. He asked to be granted a deferment due to his unique situation, but the Draft Board decided that other family members could take over his duties. So reluctantly, Lee prepared to go to war. As fate would have it though, his service in the U. S. Army Air Corps led him to the woman with whom he shared the rest of his life.

On March 7, 1942, Lee and thirty-one other men from Roger Mills County entered the military. Twenty-eight of them were drafted while the other three volunteered. According to a local newspaper, on the morning of their departure by bus for Fort Sill, Oklahoma, the Cheyenne High-School band assembled at the Selective Service office to send them off with a quick concert.

As a member of the U. S. Army Air Corps, Lee traveled from Fort Sill to Sheppard Field in Wichita Falls, Texas, for basic training. He remained there from March 18, 1942 until May 1942. He then transferred to MacDill Field near Tampa, Florida, where he was assigned to the engine change crew. On June 27, 1942, after only a few weeks in Florida, Lee transferred to Walla Walla, Washington, arriving there after a five-day train trip. In Walla Walla, he became a mail carrier traveling back and forth between the base at Walla Walla and a new base being constructed at Pendleton, Oregon. Two months later, Lee transferred to Fort Dix, New Jersey, in preparation of going overseas.

On September 14, 1942, Lee arrived in England. Then in November, he was put in charge of quarters. He had to wake up the troops, make sure they made their bunks and cleaned the barracks. At night he made sure the lights were out because everything had to be blacked out. Lee said those duties reminded him of the things he did at home.

Lee was stationed at Bassingbourne, Airfield near Royston, England, as part of the 323rd Bomb Squadron 91st Bombardment Group (Heavy). The bombers’ mission was to bomb the enemy’s essential sites such as “aircraft factories, airfields, and oil facilities” (“91st Bomb Group”). Lee’s job was in the kitchen, and he wrote home to his family that he was “flying the China Clipper” meaning the dishwasher.

While his kitchen assignment kept him out of harm’s way for the most part, Lee was still part of the Army Air Corps, which was actively engaged in war. Lee kept a diary of his time in England, and he recorded events in the war. On Saturday, January 2, 1943, he wrote, “Our boys went on a raid. One plane was lost.” Then he listed the names of the men who died. On Monday, January 18, 1943, he wrote of a bombing raid by the Germans. He said, “Day raid on London. Schoolhouse was bombed. Several were killed.”

On March 4 and April 1, 1943, Lee recorded raids, planes lost, and men dead. In his diary, he also wrote several entries about being on alert. For instance, on April 4, 1943, he wrote, “We had an alert at 10:50 p.m. until 11: 50 p. m. One plane was heard overhead.” By the end of the year, his entries about bombings and raids had become somewhat routine. His tone was almost nonchalant in his diary. On December 10, 1943, he wrote, “Jerry [Germans] was over tonight and dropped some bombs.”

Lee’s assignment in England brought some unique opportunities. His diary notes that the king and queen of England visited the base on May 26, 1943, and the movie star Clark Gable came to the airfield and broadcast a radio show on June 5, 1943. He spent a lot of time riding a bike around the English countryside, and in a letter home to his family, he said England looked like the scenes described by William Shakespeare. Only one entry in his diary indicates how he felt about the military. On Wednesday, July 28, he said, “Hot today, and another day in the Army. I will be damn glad to get out of this place.” Otherwise, he was quite stoic about his situation. He even told his family that he was not homesick although many other soldiers were.

Lee wrote home to his parents quite frequently, and his daughters inherited the letters. His letters revealed not only the life of a soldier but also Lee’s concern for his farming operation, which he attempted to manage from a distance. He wrote many letters using V-Mail. V-Mail, postage created to aid communication between military personnel and their loved ones back home, was free. Both soldiers and their families could use V-Mail. The letters were microfilmed, and smaller, yet readable, copies of the letters were produced and mailed. Reducing the size of the letters had a practical purpose: the overseas mail weighed less, it created room for shipping articles needed in the war effort, and it was faster than sending regular mail (“Resizing Lifelines”).

Lee’s letters indicate that he earned $14 a month upon entry into the Army, but by April 1944, he was earning $60 per month, although he had to pay for his laundry. He was apparently frugal because Lee wired money home so he would have funds to invest in his farming operation. Even with saving for the future, Lee still had money for entertainment. His diary suggests that he often took a friend to the movies.

Lee met his future bride, local girl Betty Shurey, through acquaintances. In his diary, he started the year calling her his friend, but that soon turned to using her first name. Almost every entry tells something about Betty, from their bike rides to her buying a new dress. By the end of the diary, they are spending all their free time together.

Not surprising, Lee proposed to Betty, but marrying someone from a foreign country, even if the country was a U. S. ally, was not a simple process. Lee had to complete an application to marry Betty two months prior to the marriage. Betty had to write a letter to accompany the application stating that she agreed to the marriage. A regimental commander would grant permission for them to marry if “the marriage contemplated would not bring discredit to the military service” (Circular #66). The rules for marrying in a foreign country went on to forbid “special living arrangements or…any special privileges different from those enjoyed by single men or women of the command.” The rules stated that marriage to U. S. military personnel did not make a foreign person a U. S. citizen.

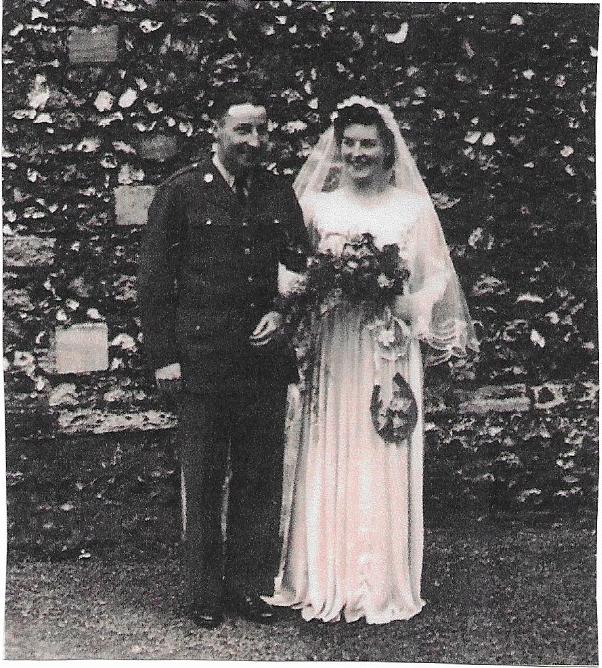

Lee and Betty received permission to marry but had to postpone the wedding for two weeks due to the fact that Lee was quarantined because of the D-Day invasion. Finally on June 24, 1944, they were wed at the Royston Parrish Church. The local newspaper, the Herts and Cambs Reporter and Royston Crow, reported the wedding as “another link in the ever increasing chain of friendship between the United States of America and Great Britain” as if it were a diplomatic union. The article went on to describe Betty’s wedding dress, veil, and bouquet as well as her matron of honor’s dress and headdress. The article also said that the bride and groom received two horseshoes, apparently for good luck.

On May 8, 1945, Lee heard the European Victory announcement on the BBC radio broadcast, so it was not long before he was headed home. He left England on August 7, 1945, without Betty. It was another nine months before she was able to join him in the United States. After stops in Drew Field in Tampa, Florida; Camp Shelby, Mississippi; and Camp Chaffee, Arkansas, Lee receive his discharge on September 17, 1945. Lee received the following medals: Honorable Service Medal, Army Presidential Unit Citation, European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, World War II Victory Medal, and Army Good Conduct Medal.

After his discharge Lee headed back to Leedey to see his family and resume his farming operation. Following his return home, Lee used his GI Bill benefits to study mechanical engineering, livestock production, and animal health. He lent a hand to his aging parents and remodeled his house for Betty, who arrived by ship in New York City a several months later. Her reception in the United States was less than cordial. A group of protesters threw eggs and rotten fruits and vegetables at her and other war brides when they left the ship. Fortunately a policeman was on hand to escort them away from the rude Americans. From New York, Betty rode a train to Woodward, Oklahoma, where Lee was waiting to take her home to Leedey to start her new life.

Adjustment to rural Oklahoma had its trials. For instance, Betty’s accent labeled her as an outsider, and she had never lived on a farm. However, she persevered, made friends, and gained her American citizenship. She often quipped that because she was able to pass the citizenship test, she knew more American history than the Americans did.

Lee and Betty lived the rest of their lives on the farm near Leedey and raised two daughters. Lee died October 19, 1980, and Betty passed away October 26, 2017. Their daughters, Dixie Ferrell and Betsy James, remain in western Oklahoma and treasure the legacy of their parents.

To view a collection of Lee’s letters home and Betty’s letters to Lee’s parents, go to https://westernoklahomahistoricalsociety.org/document-category/lee-clem-world-war-ii-collection/.

Sources

“Circular #66, European Theater of Operations, United States Army.” 22 Oct. 1942.

“91st Bomb Group The Ragged Irregulars.” American Air Museum in Britain. 2020. Imperial War Museum. https://www.americanairmuseum.com/unit/544

“Resizing Lifelines—Planning V-Mail.” Smithsonian National Postal Museum. n.d. Smithsonian Institute.

https://postalmuseum.si.edu/exhibitions/victory-mail-introducing-lifelines-planning-v-mail