by Mary Fern Carpenter

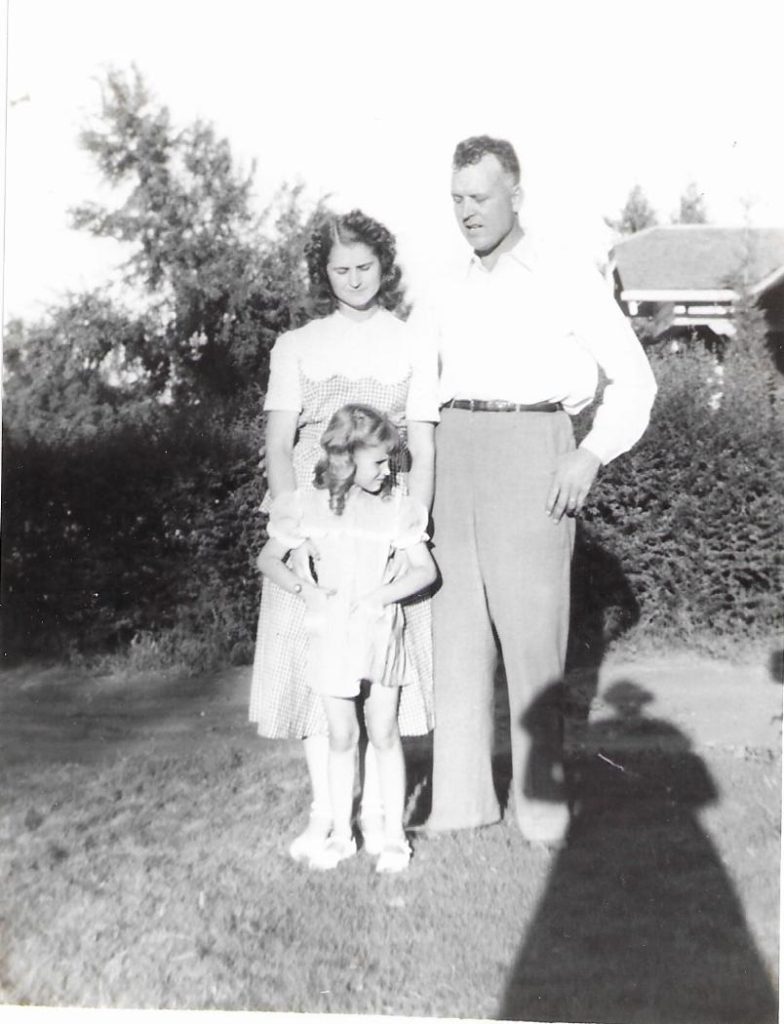

If I could turn back time, it would be to 1948 when I was five years old and my parents (George and Lucy Stansberry) and I moved back to Elk City, Oklahoma. My dad had been born in Elk City in 1912, but he and Mom had moved to Hermosa Beach, California, at the onset of World War II where Dad was a foreman in the shipyards. Then I was born in Hermosa Beach in 1943. In 1948 the war was over, and my parents longed to move closer to family and so headed to Oklahoma.

Back in Elk City they soon purchased a large parcel of land right on Route 66 just east of Ackley Baseball Park (what kids today call The Rock). I’m sure the land wasn’t too expensive at the time since there wasn’t much else on that stretch of town on the highway. Throughout my whole kid life from then on, Route 66 intertwined its life with mine. At night the hum of cars whizzing by even provided my lullaby—with an occasional clash of cymbals from a gigantic semi.

On the east side of our property was our little pink house surrounded by a circle of trees. There was a white rail fence around our yard and pink four o’clocks growing by a small front. Our porch was small, but it could accommodate two chairs which it did when my Grandfather Stansberry walked to our house for a visit. He was a tall, lanky man with thick white hair who always wore khaki pants and shirts and a pair of suspenders. He enjoyed coming to our house to count cars. Sometimes he also classified them. So many trucks, so many sedans, so many pickups, and so on. The endless stream awed him. I, in turn, marveled at his ability to count and spit tobacco at the same time.

After Grandpa was satisfied that he’d done adequate research for the evening, he began his stories. Scary stories that would have kept an imaginative little girl awake all night had it not been for that lullaby of vehicles. And I reveled in the thought that each of those cars held a story of its own. All those people were going places and having adventures.

Before I had lived on Route 66, I had traveled it myself a few times and had some knowledge of what the experience was like. At least the portion that ran from California to western Oklahoma. The war had just ended so we still drove on retread tires. That meant frequent stops to change flats. I vaguely remember a steep pass that severely challenged our radiator. And once, even though we came prepared with the standard canvas bags filled with water hanging from the car grille, we had trouble putting a fire out under the hood.

Traveling the highway included seeing a montage of Navajos selling baskets, pottery, and woven blankets beside the road. Then there were the roadside hustlers that advertised snakes and tigers and various curiosities. Thankfully, we never stopped at those. There were quaint motor courts and cozy diners. And, of course, the Burma Shave signs were always welcomed as a break from long, barren stretches of nothingness.

At some point Hodges IGA grocery store popped up just east of a culvert that separated our properties. I cherished the times Mom gave me a few coins to go to the store on my own. I’d walk or ride my bike or swing by a rope that hung in one of our elm trees to cross the ravine doing my best Tarzan yell. Then I’d generally buy a Dr. Pepper, a Butterfinger, and a comic book or movie magazine. That could keep me occupied for hours.

Down the east side of the highway was the old Community Hospital, the first co-op hospital in the country founded by Dr. M. Shadid. That’s where my dad worked as head maintenance engineer for 25 years. My brother Mark was born there when I was thirteen, so we were both only children. Later we each had summer jobs there in our teens. My two sons Andrew and Chris were born on that site as well as Mark’s three children: Joe, Matt, and Aubrey. Several years later my grandchildren Bailey and Jacob were born at this location. However, somewhere along the way new buildings were constructed and the name changed to Great Plains Regional Meidcal.

But the south side of the highway remained vacant for a long time. It was just an open field. It was in those empty fields that traveling medicine shows used to set up to entertain the public and to sell their wares. I remember the old Hadacol Medicine Show. Hadacol was supposed to cure just about anything. Lots people swore by it. Since it was about 98% alcohol, those people probably didn’t know if they were sick or not. In addition to the vaudeville show Hadacol put on, they also had drawings. Townspeople drove their cars onto the grass and bought boxes filled with taffy candy and a numbered slip of paper. Then the winning numbers were called out. Mom was excited when her number was shouted out and she found she had won a tea kettle. Only thing I ever remember my family winning.

Eventually, a little ways down the south side of the road Mr. Royse had his filling station. A Texaco if I remember right. Mr. Royse and Mr. Hodge were not only good businessmen but also good neighbors, and we were glad to have them nearby. You see, not all of those who traveled Route 66 had vehicles. It was not unusual for someone to be trying to thumb a ride in front of our house. Most of those hitchhikers were just hapless folks doing the best they could. But once in a while, one would give us a menacing vibe.

I recall one such young man who was making Mom nervous. She could see him from the kitchen window and could see that he kept eyeing our house. When Dad drove back to work after his lunch break, the hitchhiker walked around to the back entrance of the house. Salty, our part terrier/part Chihuahua dog, started barking furiously, confirming the man was up to no good.

Soon he knocked. Mother didn’t open the door. Just talked through the glass at the top. She asked what he wanted. He replied that he wanted a drink of water. Mother told him to feel free to drink from our water hydrant outside. We often did. But he insisted on having a cup. Then Mother suggested he go to the grocery store to the drinking fountain.

He said, “They don’t have a drinking fountain.”

Mother knew that wasn’t true, so this time she raised the barrel of Daddy’s shotgun up where he could see it and said, “Well, I know they have water at the filling station across the street.”

The hitchhiker just took off in a run, only not toward the station, but west out of town. Mom said he just ran until he was out of sight. I bragged to my girlfriends at school about Mom’s bravery. They were duly impressed and called her Shotgun Lucy for a long time after that.

Eventually, Elk City decided to take advantage of all those tourists who could afford to take vacations in the 1950s via the festive highway. A line of motels sprang up on that previously empty stretch with names such as the Sands, the Flamingo, and the Palomino. All of them were ablaze with bright, glitzy neon signs. Mom loved it! She said it was like living in Las Vegas.

Sometimes even movie stars stopped in our town and stayed in one of those motels. The Flamingo Motel was directly across from us, and one time the owner and good friend Ernie Bell crossed the highway to tell Mom and to look over at the swimming pool at the man with the red-gold hair. It was Clu Gulgager of the “The Virginian” fame. Mom and I never missed that television show. My brother Mark was around by then and remembers Ernie taking him across the street to meet Clu and his kids. “Yep,” Mom said. “Little Las Vegas.”

Being close to Ackley Baseball Park meant that twice a year our place became the center for large family gatherings and great excitement. On the 4th of July we could see the city fireworks display just fine from our backyard. Our whole extended family and many friends came to our house to celebrate. Mom made sandwiches and Kool-Aid. Dad cranked the ice cream freezer. Everybody brought food of some kind. Those are some of my happiest memories. Only Salty didn’t enjoy it. The noise of firecrackers and Roman candles scared her. She always sneaked into one of our visitor’s cars and hid. We’d have to find her before anyone left for home.

The other occasion rife with excitement was when the Beutler Brothers Rodeo came to Ackley Park for Labor Day. There was always a kind of electricity in the air that was palpable. Cowboys were everywhere. A couple even jumped their horses across our fences and right through our yard, Salty barking and nipping at their heels. Once again we’d be the place to rendezvous for relatives and friends so they could go to the rodeo. One year my Great Aunt Cora came all the way from California to visit her brother Grandpa Stansberry and to see the famous rodeo.

That turned out to be the year one of the bucking broncos broke loose and leaped into the stands, frighteningly close to Great Aunt Cora. It was also the time renowned rodeo clown Hoyt Hefner was seriously injured during the incident. We were all worried that this might have been too much for the dignified elderly lady. We hovered over her and waited anxiously for her response. With her frail hand she drew wisps of white hair off her neck and into the regal upswept do she always wore. She squared her shoulders and took a deep breath. “Exhilarating,” she pronounced. “Absolutely exhilarating. Let’s go again tomorrow night.”

The city leaders quickly decided that was too exhilarating and immediately began plans for new rodeo grounds. Ackley Park would be reserved for baseball, 4th of July, and in 1980 it was the location for the first Fiddlers’ Convention in Elk City. At the time it was called Western Oklahoma Bluegrass and Country Music Festival. My dad George Stansberry and some of his musician friends organized what would become an annual event called The State Fiddlers’ Convention. Although it moved indoors after the first year, its hugely successful kickoff started on Route 66.

Well past my childhood, Elk City spread west of Ackley Park on Route 66 and added our beautiful park and the museum complex. In 1977 my mother Lucy Stansberry went to work at the Old Town Museum where she became curator for over thirty years. She watched the complex grow and the National Route 66 Museum built and dedicated in 1998 so close to the area where I grew up. On September 19, 2010, she was posthumously inducted into the Route 66 Hall of Fame at the Oklahoma Route 66 Museum in Clinton. As my brother said at the induction ceremony, “Mom’s still getting her kicks on Route 66.”

The iconic landmarks of the Flamingo Restaurant run so efficiently by Phil Bell and staff and our beloved Country Dove established by Glenna Hollis and Kay Farmer would also come after I was no longer a child. Like the traffic on the highway, the businesses alongside are always in flux.

It has always given me great pride to think that my hometown of Elk City is right here on the road that was once the main artery of the nation. It is a mystic road that still attracts visitors from all over the world who seek a piece of America the way it was. You see, Route 66 is not just a geographic location. It’s a journey back in time, and for me personally, it carries with it some the fondest memories of my childhood.