by Judy Haught

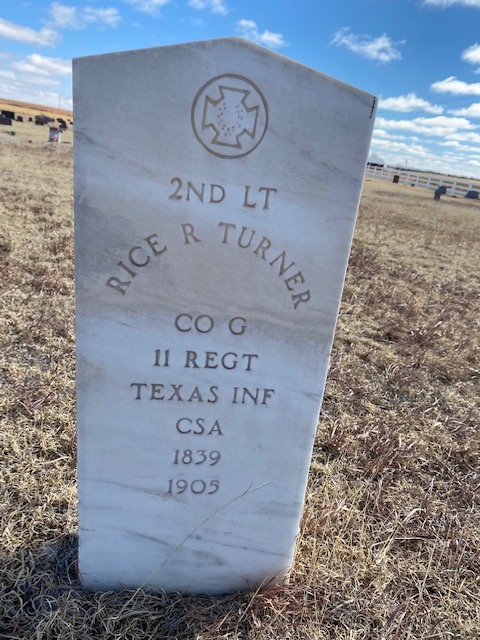

A stroll through Lone Oak Cemetery near Sayre, Oklahoma, will reveal the graves of several veterans, among them a number of graves of Confederate soldiers. A Confederate grave is easy to spot. The gravestone will have a pointed top and a Southern Cross of Honor engraved in the stone. Legend has it that Confederate gravestones have pointed tops to keep Yankees from sitting on them. The Southern Cross of Honor was originally bestowed to Confederate soldiers as a medal. It was the Confederate version of the Union Medal of Honor. Later the United States Veterans Administration issued gravestones for Confederate veterans with the cross engraved on them. Occasionally a Confederate grave will also have a metal version of the cross alongside the gravestone.

One of the Confederate veterans buried at Lone Oak Cemetery is Rice R. Turner. While details of Turner’s life are sketchy, several facts can be gleaned from U. S. Census Records, the National Park Service, and Texas history websites. He was born in Mississippi in 1839. He joined the 11th Confederate Infantry in Texas on February 26, 1862. Texas seceded from the Union soon after Abraham Lincoln was elected President in 1861, even before the war officially started. The 11th Texas Infantry was mustered into service in the winter of 1861-1862 near Houston. Ten companies with recruits from several Texas counties comprised the regiment. Turner was among those recruits. His rank upon joining the army was Private, but at the end of his tour of duty, his rank was 2nd Lieutenant, a fact that indicates a field promotion. A field promotion would generally be granted for outstanding service in combat, allowing a soldier to skip the traditional channels of rank and promotion.

According to the Texas State Historical Association, the 11th Texas Infantry was stationed in East Texas until August 1862. There the Texas State Penitentiary at Huntsville furnished the soldiers with “cloth for tents, knapsacks, and for some clothing.” One wonders if the soldiers had to use the cloth to sew their own clothes and equipment or possibly hire it done. The regiment went on to engage in several battles in Louisiana and Arkansas, suffering a large number of casualties. In the spring of 1864, they participated in the Red River Campaign in Louisiana. They assisted in the capture of “2,000 prisoners, 20 pieces of artillery, and 200 wagons of arms.” Then in 1865, they guarded prisoners at Tyler, Texas. The war ended in April 1865 with Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia, and the 11th Texas Infantry surrendered June 2, 1865, at Galveston, Texas. As a Confederate soldier, Turner was considered a prisoner of war by the United States. Upon signing a pledge to never serve in a “military capacity” against the United States, he was paroled and set free on July 7, 1865, at Marshall, Texas.

After the war, Turner remained in Texas and married Martha Jane Collier in 1865. The couple made their home in Pennington, Texas, despite the fact that the Reconstruction era in Texas was one of anger and tumult. Texas residents had to take a pledge of loyalty to the United States and profess the illegality of secession. Many Texas residents, primarily German immigrants and Tejanos, had been opposed to secession. Violence had erupted in the state over political disagreements, and old wounds still festered after the war. In addition, disagreements between Texas and Native Americans that had taken a back seat to the war rose up again with renewed violence.

Yet Turner and his family remained. The 1870 U. S. Census lists Turner’s profession as saddler. The Texas Land Title Abstracts indicates that Turner owned 160 acres of land in the Nacogdoches District of Angelina County, and the 1880 census lists him as a farmer. Having a stable, essential vocation could account for his remaining in Texas. Turner and Martha gave birth to nine children during the years of 1866 to 1885: John Marshall, William Pickney, Samuel Isham, Mary Lena, Florence Almarena, Leonidas Earl, Pascal Gustave, Phocion Pericles, and Amelia. Amelia is listed in the 1870 census but not in the 1880 census, a fact that could indicate she died during the years between censuses.

A fire destroyed the 1890 census, so no information on Turner and his family is available for that year. However, the 1900 census shows him living in Texola Township, Oklahoma Territory, with his son. Rice Turner died November 22, 1905, at the age of 65-66. He had received a Confederate Veteran’s pension until his death, and his wife Martha received a Confederate widow’s pension until she died December 9, 1923.

Why so many Civil War veterans moved to Oklahoma Territory is pure conjecture. Some surely came for opportunity, and others followed adult children. Perhaps some sought peace beyond the strife of war and reconstruction. Union and Confederate veterans apparently lived in harmony and even lie near one another in Beckham County cemeteries.

Sources

“Alabama, Texas, and Virginia, U.S., Confederate Pensions, 1884-1958.” Ancestry.com

26 June 2022.

“Confederate SFervice Grave Markers.” Sons of Confederate Veterans Adam Washington

Ballenger Camp #68. Sons of Confederate Veterans. http://www.schistory.net/scv/markers.htm. 26 June 2022.

“Cross, Southern Cross of Honor (Confederate States of America)” City of Grove.

http://www.cityofgroveok.gov 26 June 2022.

Derbes, Brett J. “Eleventh Texas Infantry.” Texas State Historical Society.

http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook 26 June 2022.

“Rice R. Turner.” Find a Grave. http://www.findagrave.com 26 June 2022.

“Rice R. Turner.” Fold 3. Ancestry.com 26 June 2022.“Rice R. Turner.” Texas, U. S., Land Title Abstracts, 1700-2008. Ancestry.com 26 June 20